Expressions#

Programming languages are much simpler than human languages. Nonetheless, there are some rules of grammar to learn in any language, and that is where we will begin. In this text, we are using the Python programming language. Learning the grammar rules is essential, and the same rules used in the most basic programs are also central to more sophisticated programs.

Programs contain expressions.

You can think of an expression as a recipe that returns a value. For example, this is an expression:

3 * 4

12

Notice that the Notebook displays the value. This the value that the expression returns.

An expression can describe to the computer how to combine pieces of data. In

our example, we have a multiplication expression that consists of a * symbol

between two numerical expressions. Expressions, such as 3 * 4, are

evaluated by the computer. The value (the result of evaluation) of the

last expression in each cell, 12 in this case, is displayed below the cell.

The grammar rules of a programming language are rigid. In Python, the *

symbol cannot appear twice in a row. The computer will not try to interpret an

expression that differs from its prescribed expression structures. Instead, it

will show a SyntaxError error. The Syntax of a language is its set of

grammar rules, and a SyntaxError indicates that an expression structure

doesn’t match any of the rules of the language.

For example, consider this code, and the resulting error:

3 * * 4

Cell In[2], line 1

3 * * 4

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Small changes to an expression can change its meaning entirely. Below, we

removed the space between the *’s. Because ** appears between two

numerical expressions, the expression is a well-formed exponentiation

expression (the first number raised to the power of the second: 3 times

3 times 3 times 3). The symbols * and ** are called operators, and the

values they combine are called operands.

3 ** 4

81

Walking a mile in Python’s shoes#

To think about expressions, we often need to remind ourselves what Python does when it sees the code for an expression.

We look again at:

3 * 4

12

It is an expression because it is a recipe that returns a value. We see the notebook display the value.

Now consider this expression:

3

3

It’s an expression because it returns a value. We see the notebook display the value.

More specifically, when Python sees the code 3, it generates a computer representation of the number 3.

We will use CR as a shorthand for computer representation. To repeat then,

the expression 3 causes Python to make and return a CR of the number 3.

The Notebook then makes a human-readable display for the computer representation, and shows it to us.

We will uses HR as a shorthand for human readable. You can also read HR as human representation.

In this case the HR 3 is the same as the code we typed, but this isn’t always

so. Consider the expression we saw above:

3 * 4

12

Python does the following:

makes a CR of the number 3;

makes a CR of the number 4;

multiplies the CR of 3 and the CR of 4 to get a CR of 12.

The CR of 12 is the value returned from the expression. The notebook turns

that into something that humans can read easily - the HR of 12 - which is

12.

Common Operators#

We often want to combine numerical values, and the set of operators in a programming language are designed to so that expressions can be used to express any sort of arithmetic. In Python, the following operators are essential.

Expression Type |

Operator |

Example |

Value |

|---|---|---|---|

Addition |

|

|

|

Subtraction |

|

|

|

Multiplication |

|

|

|

Division |

|

|

|

Remainder |

|

|

|

Exponentiation |

|

|

|

Operator precedence#

Python expressions obey the same familiar rules of precedence as in algebra: multiplication and division occur before addition and subtraction. Parentheses can be used to group together smaller expressions within a larger expression.

Multiplication has precedence (we do 2 * 3 before adding to 1).

1 + 2 * 3

7

We can use parentheses to group expressions that should be evaluated first.

Here we force 1 + 2 before the multiplication by 3.

(1 + 2) * 3

9

In the expression above, the 1 + 2 is a sub-expression within the whole

expression (1 + 2) * 3. When Python sees this line, it finds the expression

(1 + 2) and evaluates that to get 3. Then it evaluates 3 * 3 to get 9.

As you learn to program, you will learn to think about what Python is doing, and the logical steps it follows. Over time, you will find it easier to predict what it will do, and understand why.

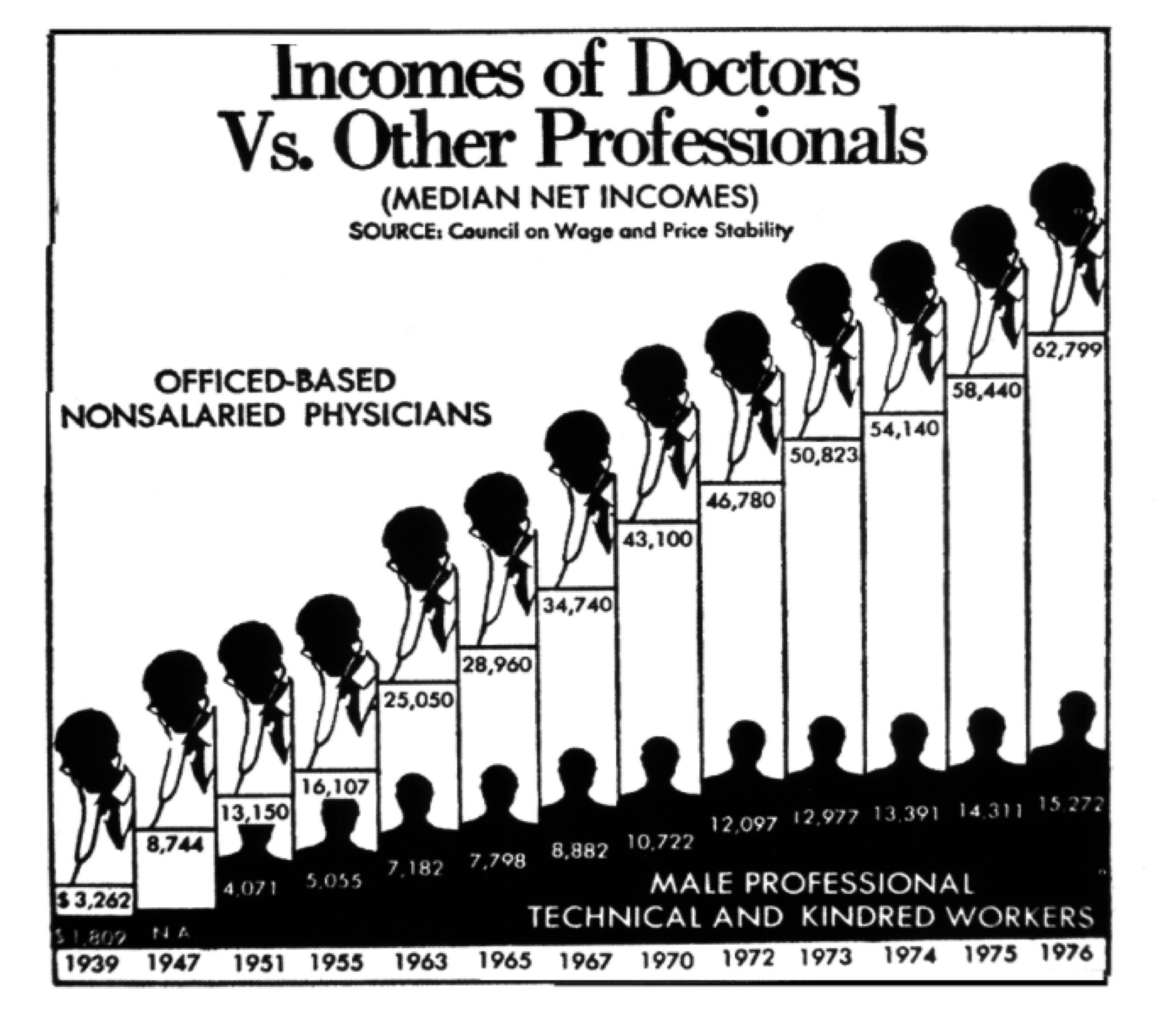

Example#

Here, from the Washington Post in the early 1980s, is a graph that attempts to compare the earnings of doctors with the earnings of other professionals over a few decades. Do we really need to see two heads (one with a stethoscope) on each bar? Edward Tufte, Professor at Yale and one of the world’s experts on visualizing quantitative information, coined the term “chartjunk” for such unnecessary embellishments. This graph is also an example of the “low data-to-ink ratio” that Tufte deplores.

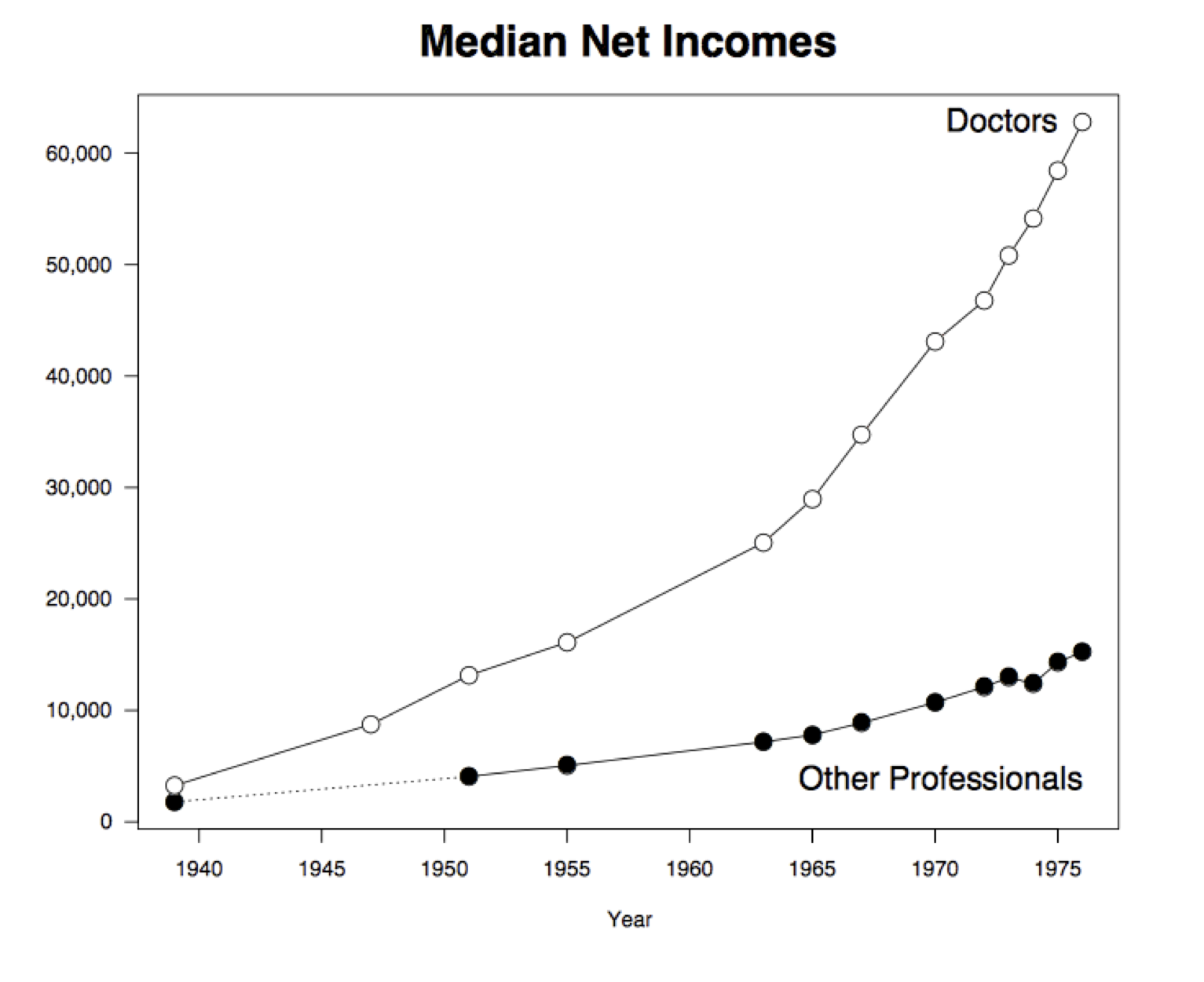

Most importantly, the horizontal axis of the graph is is not drawn to scale. This has a significant effect on the shape of the bar graphs. When drawn to scale and shorn of decoration, the graphs reveal trends that are quite different from the apparently linear growth in the original. The elegant graph below is due to Ross Ihaka, one of the originators of the statistical system R.

In the period 1939 to 1963, the doctors’ incomes went up from $3,262 to $25,050. So during that period the average increase in income per year was about $900.

(25050 - 3262)/(1963 - 1939)

907.8333333333334

In Ross Ihaka’s graph you can see that in this period, the doctors’ incomes rise roughly linearly at a fairly steady rate. That rate is about $900, as we have just calculated.

But in the period 1963 to 1976, the rate is more than three times as high:

(62799 - 25050)/(1976 - 1963)

2903.769230769231

That is why the graph rises much more steeply after 1963.

This chapter introduces many types of expressions. Learning to program involves trying out everything you learn in combination, investigating the behavior of the computer. What happens if you divide by zero? What happens if you divide twice in a row? You don’t always need to ask an expert (or the Internet); many of these details can be discovered by trying them out yourself.

Note

This page has content from the Expressions notebook of an older version of the UC Berkeley data science course. See the Berkeley course section of the license file.